The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) is responsible for building America’s “national capacity to defend against cyber-attacks and … to safeguard the ‘.gov’ networks.” Its mandate includes securing all publicly accessible Federal websites by scanning them for vulnerabilities that need to be remediated. On April 29, 2019, CISA issued Binding Operational Directive (BOD) 19-02, which tightens existing requirements for remediating vulnerabilities as well as increasing the scope of those requirements and toughening enforcement mechanisms. While we welcome CISA’s more stringent requirements, as well as the cooperation it encourages between the public and private sectors, we have some concerns that these new regulations neither go far enough nor apply the best methodology for remediating vulnerabilities.

Previous CISA Directives: The Background to BOD 19-02

BOD 19-02 is the 9th CISA directive to be issued; past ones have covered issues ranging from vulnerability remediation in general to a requirement to remove all products from a specific company (Kaspersky, named in BOD 17-01). CISA’s first BOD, BOD 15-01, was issued in 2015. It mandated regularly scheduled cyber hygiene scans for all agencies under its jurisdiction and also specified that any “critical” vulnerability, as determined by CVSS score, must be “mitigated” by the agency within 30 days of being notified about the vulnerabilities being found in the most recent cyber hygiene scan.

Due to increased DNS attacks, on January 22, 2019, CISA issued Emergency Directive 19-01. This directive forced agencies to take preventative measures against such attacks, including requiring multi-factor authorization for accounts that could change DNS information. Like other directives issued after BOD 15-01, Emergency Directive 19-01 neither altered the timeframe for dealing with “critical” vulnerabilities nor explicitly required treatment of vulnerabilities with a CVSS rating of “high.” (“Major” weaknesses had been subject to the 30-day rule, but this term was not linked to CVSS rating).

BOD 19-02: A More Detailed Look

BOD 19-02 differs from BOD 15-01, which it replaces, both in terms of scope and enforcement.

Scope

BOD 19-02 significantly reduces the time that an agency has to remediate critical vulnerabilities from 30 days to 15. It also specifies that vulnerabilities that have CVSS ratings of “high” must be remediated within 30 days. This language clarifies what is meant by “major,” but does not have the same impact as the reduction in time allotted for addressing critical issues. In all cases, the “clock” now starts earlier beginning when CISA detects the issue, not when it notifies the agency.

Enforcement

BOD 19-02 has a stronger enforcement mechanism than its predecessor. If an agency is late, CISA will send it a partially completed remediation plan, which must be returned completed within 3 business days. If needed, the CISA will speak with the agency’s CISO and other personnel to ensure compliance. While no specific sanctions or penalties are mentioned, it is clear that any such meetings will not be “social” in nature.

But Is It Enough?

While it is clear that CISA is working to harden .gov websites, questions have been raised about the directive. First, as Mounir Hahad, head of Juniper Networks’ Juniper Threat Labs states, 15 days is too long to endure “critical vulnerabilities for which proofs of concept may already be published or for which developing an exploit is trivial.” Once a vulnerability is in the wild, it can do tremendous damage in 15 days. Worse, if such vulnerability has “only” a “high” CVSS score, BOD 19-02 gives agencies 30 days to remediate it, far too long.

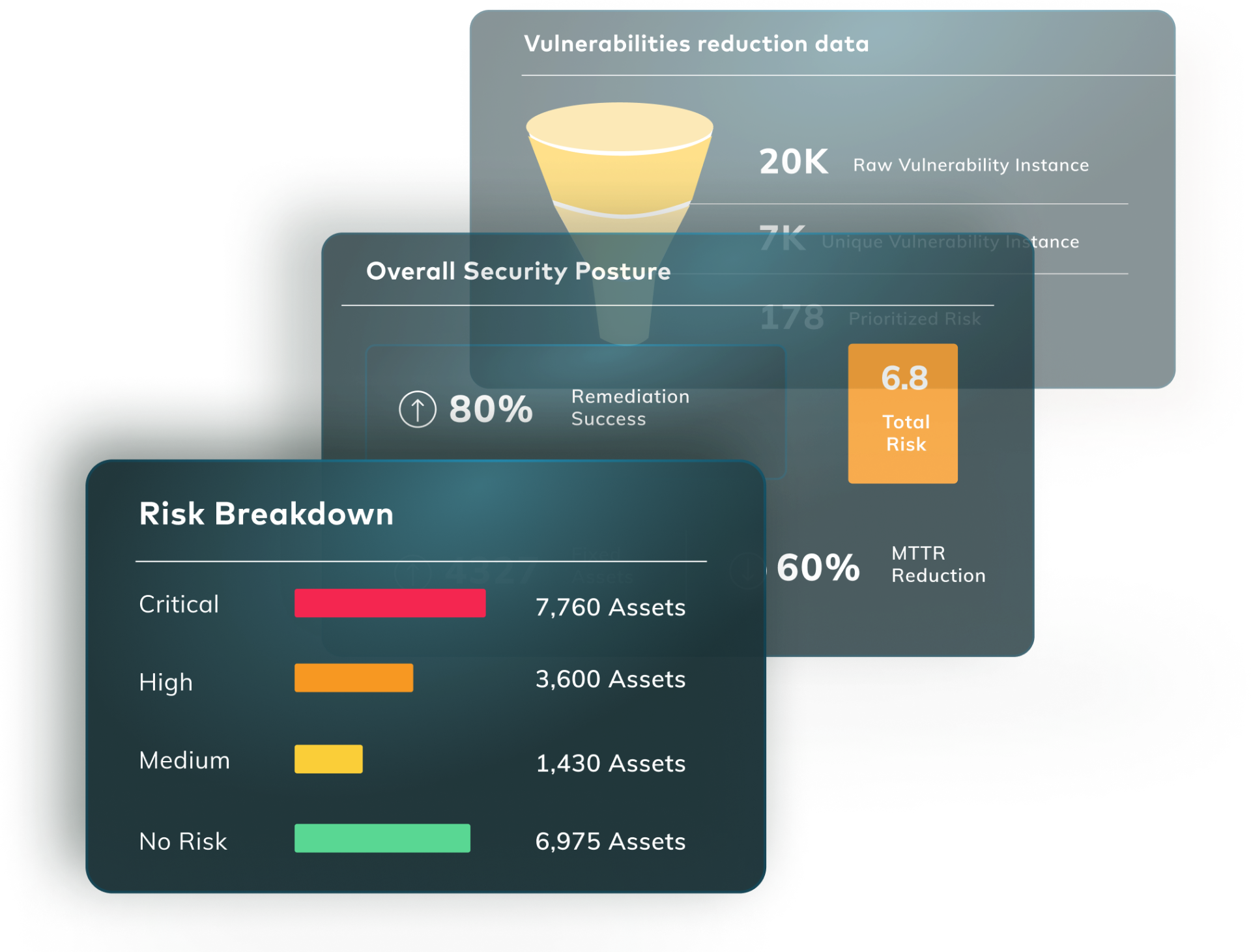

But there’s a deeper problem than just time — BOD 19-02 relies primarily on CVSS scores rather than risk-based assessment in prioritizing vulnerabilities. The risk-based approach to vulnerability management and remediation involves determining which vulnerabilities pose the greatest actual threat to a network and taking care of them first. Although the directive gives agencies some freedom in prioritizing vulnerabilities, this latitude is only in the context of the previously mentioned time limits. In practice, due to the 5-day rule this almost guarantees that “critical” vulnerabilities will be addressed first, no matter which vulnerability poses the greatest actual threat to an agency.

Additionally, the directive excludes some important items from its scope: vulnerabilities that are internal to an agency’s network including infrastructure “that enables endpoints to be accessible over the internet,” software that can only be accessed by VPNs, shared services not managed by the agency. Additionally, third-party infrastructure is out of scope, except for “cloud service provider infrastructure.” These exceptions could be problematic for any agency that is creating cloud-native apps or otherwise using a CI/CD pipeline that incorporates third-party software.

The Bottom Line: BOD 19-02 Is an Important Intermediate Step

BOD 19-02 is an important extension and replacement of previous CISA directives. We applaud the Federal government’s effort to promote cooperation between the private and public sectors and to promote quicker responses to threats. Having said that, we think that adoption of a risk-based methodology and improved security for agencies using CI/CD pipelines would significantly improve CISA’s efforts to harden Federal cybersecurity. All in all, BOD 19-02 is an important step, which we hope will be the starting point for greater network security.